Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover,

17th–18th century, inventoried 1883. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom,

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola.

Raffia, pigment; 9 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. (24 x 47 cm). Pitt Rivers Museum,

University of Oxford (1886.1.254.1)

One of the wonders of Kongo: Power and Majesty,

on view through January 3, 2016, is the group of luxury textiles finely

woven from golden palm fiber, then hand-cut and rubbed in the weaver's

hands. The result is a rich interplay of tone and texture that reminded

me at first of aerial views of crop circles cut into fields of ripening

grain.The textiles, however, are far more complex as virtuoso pieces. Their making was described with admiration by Antonio Zuchelli (1663–1716), an Italian missionary to the Kongo. He notes how the local weavers finished their cloth "with a knife they cut the cloth in the proper spots and rub it well with their hands, so that it looks like patterned velvet." Europeans compared what they saw to luxurious Italian silk velvets with elaborate woven patterns, but they admired pieces that were "so beautiful," in the words of the Portuguese sea captain Duarte Pacheco Pereira (ca. 1460–1533), "that those made in Italy do not surpass them in workmanship." What really surprised them was the way in which Kongo cloths were woven not from silk but from raffia, which made them miraculously soft to the touch. The designs were less often a source of comment, although in 1656, John Tradescant the Younger (1608–1662) described a cloth in his museum in Lambeth—now in the Pitt Rivers in Oxford—as "A Table-cloath of grass very curiously waved."

When one looks at these luxury textiles with twenty-first-century eyes, the timeless artistry of the design is particularly striking. Bands of sophisticated geometric patterns spiral across the textile surfaces, similar to the interlace patterns on Kongo ivory oliphants, which are carved from curving elephant tusks. Such repeating motifs were not merely decorative but had profound significance within Kongo society. Exhibition curator Alisa LaGamma explains in her introductory chapter to the exhibition catalogue how the spiral movement is a visual metaphor for the path taken by the dead, which is central to Kongo thought and imagining. That concept communicates through the finished designs, explaining why these were elite display pieces in Kongo society, and why they were an important component in diplomatic exchanges with the Portuguese from the fifteenth century.

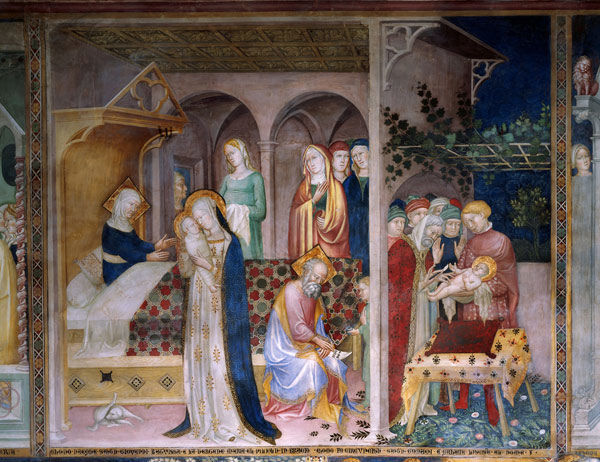

An interesting puzzle—and a prompt to further research—is the European format of the cloths themselves, which are shaped to European taste in their format and structure. Even the elaborately made pompoms at their corners imitate those made of silk or wool on European cushions. A fascinating insight into the status of luxury cushions within an Italian, early fifteenth-century context is provided by the Salimbenis' fresco from Urbino showing scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist.

Lorenzo and Giacomo Salimbeni (Italian, ca. 1374–ca. 1416). Scenes from the Life of John the Baptist (Birth and Circumcision) (detail), ca. 1416. Fresco. Oratorio di San Giovanni Battista, Urbino, Italy

The infant Saint John has been presented for circumcision by the rabbi on an Italian-made red cushion which, with the fine tablecloth and superb coverlet, shows the importance of such accessories as badges of status. This was the kind of context within which the Kongo luxury cloths were understood when they first arrived in Europe.

Some of the finest surviving Kongo cloths are still to be found in collections formed in Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Known as Kunstkammern, or "art rooms," these cabinet collections at first concentrated mostly on small-scale European treasures that were precious and intricate or demonstrated skill or virtuosity. But during the sixteenth century, in the so-called Age of Exploration, these collections diversified to explore all things curious, rare, and exotic that had been brought from an expanding range of global contacts. What were Europeans to make of what Shakespeare unforgettably called the "brave new world" opening up all around them?

From Stockholm to Florence, London to Prague, Kongo luxury cloths were preserved in court and cabinet collections formed by rulers, princes, and urban elites. The first two recorded examples appear in Prague in 1607—in the Kunstkammer of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Prague (r. 1576–1612), where they remain today—but the royal houses of Sweden and Denmark swiftly followed.

Kongo cloths are also recorded in the seventeenth century as prize pieces acquired by doctors, scientists, and scholars. The Milanese physician Ludovico Settala (1552–1633) and his son Manfredo (1600–1680) formed one of Italy's most famous scientific museums, which included several examples. There is a drawing of a folded one, annotated as "a small mat to make a cushion to sit on, made of straw of rare beauty…made in Angola or Congo." Settala's scholarly network included the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), founding director of the the Musaeum Kircherianum in Rome, who acquired pieces described in 1709 as "four mats made with admirable skill in the Kingdom of Angola….they look like a silk cloth notwithstanding they are made of very thin palm threads."

C.F. (Cesare Fiore; Italian, 1636–1702). Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover in the Catalogo del Museo Settala, mid-seventeenth century. Watercolor. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena (vol. 1, ms. 17)

Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), physician and second president of the

Royal Society—whose collection was to become the foundation of the

British Museum in 1753—owned two pieces that are listed in his

manuscript inventory and which still survive in a battered state. An

oblong cushion in much better condition, also in the British Museum, was

only acquired much later and illustrates the rise of ethnography as a

discipline in the nineteenth century, which led to the fragmentation of Kunstkammern all over Europe. It was first inventoried in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer

in 1674 but was deaccessioned by the Nationalmuseet in Copenhagen and

acquired by the Quaker and abolitionist Henry Christy (1810–1865), who

gifted it to the British Museum.

Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover,

16th–17th century, inventoried 1674. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom,

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola.

Raffia; 9 x 20 7/8 in. (23 x 53 cm). British Museum, London

But how were these cloths originally acquired? We are slowly finding

out more about the web of European dealers, the international trading

companies, and the merchants who supplied collectors, but the cultural,

political, and trading exchanges in which textiles first changed hands

in Kongo itself are still a mystery. Did European visitors bring

examples of their own cushions to Kongo and commission copies in local

materials and techniques? Or did Kongo leaders commission them as items

of commerce, exploiting new markets? Either way, their presence in

European collections from the sixteenth century attests to the

fascination they aroused as virtuoso textiles, which made distant worlds

tangible.

No comments:

Post a Comment