Sunday, September 9, 2018

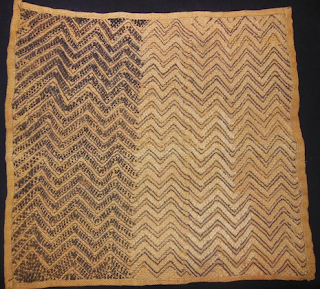

Pagne Kuba

In sub-Saharan Africa, where representative art has flourished for centuries, carvers and crafts people have typically taken for their subjects human figures, animals, plants, and elements of the natural world. Abstract art, meanwhile, has remained marginal. The textiles of the BaKuba (Kuba) people of the Democratic Republic of Congo are an exception. Although part of a tradition that stretches back 400 years, Kuba textiles have a strikingly modern look. They use improvised systems of signs, lines, colors, and textures, often in the form of complex geometric rectilinear patterns. Their appliqués are reminiscent of works by 19th- and 20th-century masters like Matisse, Picasso, Klee, Penck, and Chellida. This is no coincidence: all of those artists were inspired by Kuba design!"

"The most commonly known of the Kuba textiles are the cut-pile Shoowa or Kasai Velvets, named after the river along which the BaKuba live. Improvisation and irregularity characterize the Kasai Velvets. This is because the weaver works without a plan or preliminary sketching, though the model can occasionally be displayed on the cloth in advance using black thread. Often the design is built up from memory, repeating the most common designs and color combinations found in the region. The message conveyed is up to the artist, who is the only one who can explain what he or she intended to represent."

"Originally Kasai Velvets were used as currency, and were valuable products for trade and exchange. They could be included in the tribute villagers paid annually to the King, in the dowries of matrimonial exchanges, and in funeral gifts and offerings to the dead. They also served to embellish the royal court, cover the royal thrones, and decorate the King’s palace wall. Colonial agents and missionaries arriving in the Kuba Kingdom in the nineteenth century were fascinated by the Kasai Velvets, and encouraged women to produce more of them to adorn religious vestments for Catholic missionaries and decorate the interiors of European houses." This piece measures 18" x 20"

Friday, September 7, 2018

The Dress of Makoti

This is an example of the dress of makoti. To show respect and submission to the authority of her husband and parents-in-law, traditional practice dictated that a newly-married Xhosa woman would wear her ikhetshemiya (headcloth) low over her forehead, keep her shoulders covered, cover her hips with a blanket and wear a isishweshwe skirt and apron. She should stay with her parents-in-law for up to a year, a period during which her behaviour conveyed that she adhered to ukuhlonipha traditions of respect. Aspects of this practice are still present but are being eroded with urbanization. Head cloth, blanket and towel on loan from Siphokazi Mesele, nee Lindelwa Pamela Mbola, who wore them when she was makoti.

Blaudruck

Simplified resist-dyeing techniques were used to create a fabric of

small, white, regularly spaced patterns on a deep blue background. This

was known in Germany as 'blaudruck' (blue print). This fabric was

transformed into garments for work-wear and peasant-wear, and became

associated with European regional and Protestant dress, as well as

expressing nationalist sentiments. When German missionaries and traders

immigrated to the Eastern Cape and other parts of southern Africa during

the mid-1800s, they brought their 'blaudruck' with them and traded with

those they came in contact with. It became popular amongst women on

mission stations. This fabric was later adopted by IsiXhosa women in the

Eastern Cape to produce garments.

Indienne

One of the oldest artefacts in the isishweshwe collection, this dress is

an example of 'Indienne'. It is made of Indian cotton (chintz or

calico) and has a continuous pattern of delicate intertwined stems

bearing leaves and flowers. The dress originated on the Coromandel coast

of India in the third quarter of the 18th century. Indian chintz was

extremely popular throughout the eighteenth century, and was imported

into the Netherlands by the Dutch East India Company, thus making it

available at the Company's halfway station at the Cape.

IsiShweshwe and Colonialism

The

cloth known as amajamane, amajerimane or isishweshwe has its origins in

the East, and was originally made from cotton and blue dye from the

indigo plant. Through trade, it spread to different parts of the world

including the Cape, where it was initially worn by slaves, Khoisan and

colonialists. The earliest origins of isishweshwe can be traced back to

the craze for colourful indiennes (Indian cottons) which spread like

wildfire across Europe from the mid-1600s. The complicated techniques

for making multi-coloured indiennes in Central Europe were eventually

adapted to the use of one colour only: indigo.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

Wednesday, September 5, 2018

Raffia

Possibly Teke artist

Raffia cloth

(nkuta)

Date: Early 20th century

Medium: Raffia

Dimensions: H x W: 33.2 x 28.3 cm (13 1/16 x 11 1/8 in.)

Credit Line: Gift of S. M. Harris

Geography: Lower Congo-Kasai River region, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Object Number: 99-13-47

Search Terms:

Funerary

Trade

Object is not currently on exhibit

Woven

goods, such as cloth strips and fiber mats, were used in parts of

Africa as currency. Parties of the transaction used variations in width

and the quality of the weave as a means to negotiate value. Cloth was

also frequently used in connection with other currencies, such as brass

rods, thus lending additional leverage to the negotiation. Cloth or mats

of more or less uniform size were used for gifts, peace offerings,

payment from a son to his father upon attaining adulthood and payment

upon the birth of a child or the burial of a parent. Cloth currency was

also used as a tribute for a spouse who remained faithful or, by

contrast, as a penalty for adultery. In central Africa raffia woven

mats, stored flat or rolled into bundles, were a popular form of cloth

currency in the late 19th and early 20th century. Among the Teke

peoples, funerals of the wealthy and nobility required raffia cloths not

merely to cover the body but in abundance to ensure a proper status in

the "village of the dead."

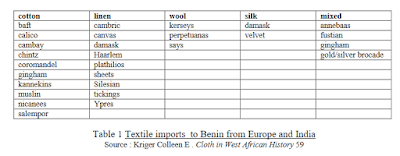

Cloths with Names’: Luxury Textile Imports in Eastern Africa, c. 1800–1885

In the nineteenth century, a vast area of eastern Africa stretching the

length of the coast and into the reaches of the Congo River was

connected by long-distance trade mostly channelled through the Omani

commercial empire based in Zanzibar. As studies have recently shown, a

critical factor driving trade in this zone was local demand for foreign

cloth; from the 1830s the majority of it was industrially made coarse

cotton sheeting from Europe and America, which largely displaced the

handwoven Indian originals. Employing archival, object, image and field

research, this article demonstrates that until 1885 luxury textiles were

as important to economic and social life in central eastern Africa,

textiles known to the Swahili as ‘cloths with names’. It identifies the

thirty or so varieties which élites — and, increasingly, the general

population — selected for status dress and gifts, instrumental in

building the commercial and socio-political networks that linked the

great region. Finally, it shows that the production and procurement of

most varieties remained in the hands of Asian textile artisans and

merchants; most prestigious and costly were striped cotton and silk

textiles handcrafted in western India, and in the southern Arabian

nation of Oman. European industrial attempts to imitate them were

hampered by several factors, including their inability to recreate the

physical features that defined luxury fabrics in this region — costly

materials, rich colours, complex designs and handwoven structures.

"Gabon" Textile

"Gabon" Textile

- Designer:

- Nathalie du Pasquier (French, born Bordeaux, 1957)

- Manufacturer:

- Rainbow, Milan

- Date:

- 1982

- Medium:

- Cotton

- Dimensions:

- 55 in. × 13 ft. 3 in. (139.7 × 403.9 cm)

- Classification:

- Textiles-Painted and Printed

- Credit Line:

- Gift of Geoffrey N. Bradfield, 1986

- Accession Number:

- 1986.398.3

- Nathalie du Pasquier was a founding member of Memphis. Barbara Radice, Sottsass’s partner, describes her as "a kind of natural decorative genius—anarchic, highly sensitive, wild, abstruse, capable of turning out extraordinary drawings at the frantic pace of a computer. . . . [Her works] are enthusiastic, explosive, exalted, elated, as striking as neon in a tropical night." Du Pasquier’s complex repeating patterns embrace all manner of influences, including African textiles, Cubism, Futurism, Art Deco, and graffiti. This work belongs to a series based on African patterns. Other designs are titled Kenya, Zaire, and Zambia.

Tuesday, September 4, 2018

Jadis

chaque

tribu

était

plus

ou

moins

spécialisée

dans

tel

ou

tel

artisanat;

les

Baduma

et

les

Mitsogo

excellaient

dans

la

confection

de

tissus

de

raphia

(ibongo),

les

Ngowè

dans

le

tissage

des

nattes

fines

à franges

(tava

yi

N gowe)

,

les

Batsangui

dans

le

travail

du

fer

(imyanga).

Ainsi,

jusqu'à

ces

derniers

temps,

les

Adyumba

étaient

renommés

comme

fabriquants

de

poterie

(ambono).

Sunday, September 2, 2018

Saturday, September 1, 2018

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Sunday, August 19, 2018

Les raphia Haut Ogooue

appelés suivant leur grandeur: Latsoulou (tout petit), Lapogho (un peu plus grand). ll en existe en fibres plus grossières tel le "Nta", c'est un pagne de 21 mètres pouvant servir de linceul. Les nattes étaient soit Okouraga (pour le séchage de ..

Le raphia chez les téké

Le raphia est un tissu d´origine Batéké, confectionner à partir des fibres très fines de palmiers en bordures de rivières, "mfoumfoulou". La feuille d´ananas fournissait des fils d´une grande finesse, plus clairs que les folioles de palmiers, mais aussi plus courts. L´on se sert généralement de jeunes feuilles de palmiers. On le tisse à sec après une opération de décorticage.

Teinté de quelques franges de fibre rouge, il est réservé aux dignitaires. Les pagnes plus larges sont de fabrication tardive, composés de quatre rangées de pièces de taille variées, cousues par une couture rabattue, ménagent autant de rangs de franges. Des plis permettent d´utiliser les deux côtés frangés de chaque pièce, afin d´augmenter l´épaisseur de cette parure.

Le raphia est aussi réservé aux grandes manifestations, pour les rites et comme tenues cache sexe (bilielé). On trouve cependant tout une variété de design attribuée au tissu en raphia. Les Batékés par exemple, présentent parmi tant d´autres échantillons,

- Mpou, ndzou, indzindjou : Généralement, pagnes réservés aux dignitaires, de par leur appellation mpou qui révèle le pouvoir, la puissance reflètant le Nzam´a mpou c´est à dire le "Dieu tout puissant",

- Mfoumfoulou : tissu raphia de fibres très fines,

- Tergal : À cause du tissage qui ressemble à la technique utilisée, comparée au tissu tergal.

- Ndouo na : Dont la confection à quatre franges de fibres reflète une couture très rabattue du tissu raphia.

- Limi : Ainsi appelé à cause de sa confection qui fait ressortir des stries saillantes comparables à celle d´une lime à étancher les couteaux et bien d´autres instruments.

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Anta

Le

tissage

de

raphia

produisait

des

couvertures

grossières

(anta),

des

caloUes,

et

des

pièces

plus

fines

(pogo)

qu'on

cousait,

jusqu'à

douze

ensemble

pour

faIre

des

toges

pour

les

hommes

et

des

pagnes

noués

sous

les

bras

pour

les

femmes.

Ces

tissus

de

raphia

étaient

le

principal

objet

d'échange

extérieur

avec

les

Mbochi,

les

Téké

de

l'Alima,

les

Kou-

kouya.

II

y

avait

des

marchés

intérieurs

pour

la

viande,

les

poulets,

les

marmites

en

terre,

les

calebasses.

Les

Téké

fabriquaient

du

sel

végétal.

kipali

Le raphia, au contraire, était beaucoup plus intégré à l’ensemble de la formation sociale au niveau de tous les groupes de filiation et de résidence. Il finit par s’imposer à son tour comme monnaie principale (ou peut-être à le redevenir). Diverses étapes marquèrent le processus. On connut d’abord les nta (= 30 tissus simples). 50 nta. Puis, Une compensation matrimoniale valait ce furent les pagnes bvarika (= 15 tissus). Une compensation valait 30 bvarika (43). Énfin les nzwuona. Une compen- sation s’élevait à 7 mubuoni, soit 140 nzwuona. L’adultère: 100 nzwuona (donc en baisse relative). Quand on sait qu’un nzwuona est formé de 16 tissus simples ntsulu, il est facile de déduire que la compensation de mariage finale .?‘était accrue considérablement (malgré l’incertitude qui pèse sur certains chiffres). D’autre part, nous trouvons confirmation de la spécialisation et du développement croissant du tissage. “On a changé de tissus de raphia - comme monnaie - parce qu’ils étaient de plus en plus beaux. ”

Nta

Pour

notre

interlocuteur,

un

nta

comprenait

alors

30

tissus

de

raphia

simples,

soit

plus

d’une

semaine

de

travail,

en

comptant

le

ramassage,

la

préparation

du

raphia,

le

tissage.

Sur

ces

bases,

une

houe

équivalait

à

une

semaine

et

demie,

une

machette

à

une

demi-semaine.

On

a

donc

de

fortes

concentrations

de

travail

relatives.

Ce

qui

importe

n’est

pas

d’imaginer

un

tisserand

seul

au

monde

en

train

de

tisser,

mais

d’éprouver

la

réalisation

véritable

d’un

tel

surplus

dans

la

formation

sociale.

L’investissement productif trouvait vite ses limites.

L’investissement productif trouvait vite ses limites.

Mantsiene

nta nzwouna semi specialisees

Les riches (quand ils se distinguent) (nta, nzwuona) et sont faits par - des hommes semi-spécialisés. Les pagnes ordinaires (bvarika) par- viennent aux femmes, enfants et subordonnés pauvres par réparti- tion des chefs de hameaux. On peut ajouter deux considérations: chaque système dominant 111: puis II, englobe aussi des biens tissés des systèmes inferieurs. Ainsi II comprendra aussi des bvarika et II incluera toutes les formes de pagnes existantes. Cependant, les pagnes englobés sont alors, malgré le maintien de leurs dénominations, associés à des statuts opposés dans la production comme dans la répartition. Comme le résuma fort pertinemment notre orateur, “tous ces pagnes, nous les avons connus dans nos dots anciennes” (en met- tant à part le pagne de la panthère, qui peut servir dans le ma- riage d’un seigneur du ciel 1. Quand on sait 1’ ampleur des pres- tations funéraires en pagnes, on mesure combien le tissage cris- tallise directement le surtravail féminin (en particulier agricole) mais aussi le travail masculin (Ngoulou 198

raphia

BRANCHES

D’ACTIVITE

ANNEXES

Les

pièces

de

raphia

tissées

avec

cet

instrument

sont

petites:

le

module

ordinaire

est

de

45

cm

sur

75

cm.

C’est

en

cousant

en-

suite

ces

rectangles

qu’on

confectionnera

des

pagnes

de

taille

variée.

Ce

procédé

est

identique

à

celui

que

décrivait

l’ethnologue

italien

Pecile

(“un

piccolo

telajo

assai

ingegnoso,

fatto

su110

stesso

principio

dei

nostri

telai

primitive,

serve

a

tessere

i

quadrati

di

stoffa

cui

‘accennai

e

che

vengono

poi

cuciti

insieme”:

1887:450).

J’aurai

l’obligation

de

revenir

plus

en

détail

sur

les

diverses

utilisations

des

tissus,

étant

donné

l’importance

qu’ils

avaient

tant

dans

l’économie

interne

des

Kukuya

que

dans

leurs

exportations

;

rappelons

seulement

pour

l’instant

les

deux

usages

principaux

des

‘pagnes

ou

tissus

de

raphia

à

l’intérieur

du

pla-

teau:

on

les

accumulait

pour

former

les

compensations

matrimo-

niales

et

les

amendes

de

‘toute

nature.

Ces

tissus

restaient

toujours

convertibles

en

ressources

alimentaires.

On

distinguait

entre

deux

catégories

de

pagnes

de

raphia:

d’une

part

les

nombreuses

varié-

tés

courantes,

faites

d’une

combinaison

de

plusieurs

tissus

simples

(litsulu),

vé

aux

d’autre

part

le

ntango

(“tissu

de

la

panthère”),

réser-

seigneurs

du

ciel.

Ce

dernier

est,

lui

aussi,

composé,

comme

l’exige

le

caractère

du

métier

à

tisser,’

de

plusieurs

pagnes

ayant

les

dimensions

du

module;

mais

ceux-ci

sont

richement

déco-

rés

suivant

des

motifs

connus

et

relativement

fixés.

En

ce

cas,

la

“pièce”

de

base

de

ce

remarquable

ensemble

se

nomme

litsulu

li

ngo.

La

composition

du

n)ango

réclame

une

technique

beaucoup

plus

longue

et

élaborée,

necessltant

la

connaissance

des

couleurs

végétales

servant

à

inscrire

les

motifs.

Raphia

Un seigneur du ciel et de la terre Akolo il porte son raphia, il tient son balaie de justice, sa hache rituel.

Ntango

Le pagne porté exclusivement par les chefs, Nta qui veut dire pagne et Ngo panthère. Décoré avec les motif de la panthère, la représentation des champs de manioc et parfois les objets mpu. Ce produ, Seul lit remarquable eu égard a la technique presque immuable se trouve réservé aux Seigneur du ciel. Seul les experts étaient en mesure de faire un tango. (les kukuya )

October 2, 2015

Dora Thornton, Curator of Renaissance Europe and the Waddesdon Bequest, British Museum

Dora Thornton, Curator of Renaissance Europe and the Waddesdon Bequest, British Museum

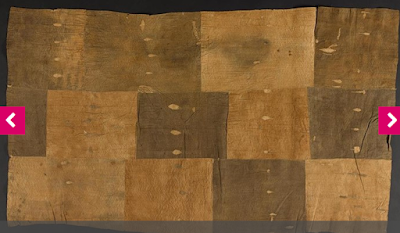

Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover,

17th–18th century, inventoried 1883. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom,

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola.

Raffia, pigment; 9 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. (24 x 47 cm). Pitt Rivers Museum,

University of Oxford (1886.1.254.1)

One of the wonders of Kongo: Power and Majesty,

on view through January 3, 2016, is the group of luxury textiles finely

woven from golden palm fiber, then hand-cut and rubbed in the weaver's

hands. The result is a rich interplay of tone and texture that reminded

me at first of aerial views of crop circles cut into fields of ripening

grain.The textiles, however, are far more complex as virtuoso pieces. Their making was described with admiration by Antonio Zuchelli (1663–1716), an Italian missionary to the Kongo. He notes how the local weavers finished their cloth "with a knife they cut the cloth in the proper spots and rub it well with their hands, so that it looks like patterned velvet." Europeans compared what they saw to luxurious Italian silk velvets with elaborate woven patterns, but they admired pieces that were "so beautiful," in the words of the Portuguese sea captain Duarte Pacheco Pereira (ca. 1460–1533), "that those made in Italy do not surpass them in workmanship." What really surprised them was the way in which Kongo cloths were woven not from silk but from raffia, which made them miraculously soft to the touch. The designs were less often a source of comment, although in 1656, John Tradescant the Younger (1608–1662) described a cloth in his museum in Lambeth—now in the Pitt Rivers in Oxford—as "A Table-cloath of grass very curiously waved."

When one looks at these luxury textiles with twenty-first-century eyes, the timeless artistry of the design is particularly striking. Bands of sophisticated geometric patterns spiral across the textile surfaces, similar to the interlace patterns on Kongo ivory oliphants, which are carved from curving elephant tusks. Such repeating motifs were not merely decorative but had profound significance within Kongo society. Exhibition curator Alisa LaGamma explains in her introductory chapter to the exhibition catalogue how the spiral movement is a visual metaphor for the path taken by the dead, which is central to Kongo thought and imagining. That concept communicates through the finished designs, explaining why these were elite display pieces in Kongo society, and why they were an important component in diplomatic exchanges with the Portuguese from the fifteenth century.

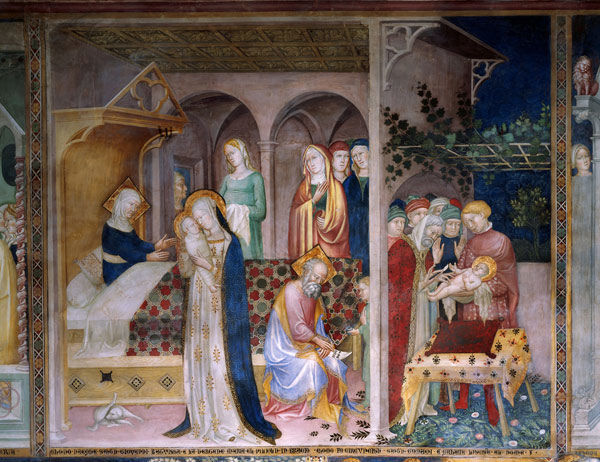

An interesting puzzle—and a prompt to further research—is the European format of the cloths themselves, which are shaped to European taste in their format and structure. Even the elaborately made pompoms at their corners imitate those made of silk or wool on European cushions. A fascinating insight into the status of luxury cushions within an Italian, early fifteenth-century context is provided by the Salimbenis' fresco from Urbino showing scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist.

Lorenzo and Giacomo Salimbeni (Italian, ca. 1374–ca. 1416). Scenes from the Life of John the Baptist (Birth and Circumcision) (detail), ca. 1416. Fresco. Oratorio di San Giovanni Battista, Urbino, Italy

The infant Saint John has been presented for circumcision by the rabbi on an Italian-made red cushion which, with the fine tablecloth and superb coverlet, shows the importance of such accessories as badges of status. This was the kind of context within which the Kongo luxury cloths were understood when they first arrived in Europe.

Some of the finest surviving Kongo cloths are still to be found in collections formed in Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Known as Kunstkammern, or "art rooms," these cabinet collections at first concentrated mostly on small-scale European treasures that were precious and intricate or demonstrated skill or virtuosity. But during the sixteenth century, in the so-called Age of Exploration, these collections diversified to explore all things curious, rare, and exotic that had been brought from an expanding range of global contacts. What were Europeans to make of what Shakespeare unforgettably called the "brave new world" opening up all around them?

From Stockholm to Florence, London to Prague, Kongo luxury cloths were preserved in court and cabinet collections formed by rulers, princes, and urban elites. The first two recorded examples appear in Prague in 1607—in the Kunstkammer of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Prague (r. 1576–1612), where they remain today—but the royal houses of Sweden and Denmark swiftly followed.

Kongo cloths are also recorded in the seventeenth century as prize pieces acquired by doctors, scientists, and scholars. The Milanese physician Ludovico Settala (1552–1633) and his son Manfredo (1600–1680) formed one of Italy's most famous scientific museums, which included several examples. There is a drawing of a folded one, annotated as "a small mat to make a cushion to sit on, made of straw of rare beauty…made in Angola or Congo." Settala's scholarly network included the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), founding director of the the Musaeum Kircherianum in Rome, who acquired pieces described in 1709 as "four mats made with admirable skill in the Kingdom of Angola….they look like a silk cloth notwithstanding they are made of very thin palm threads."

C.F. (Cesare Fiore; Italian, 1636–1702). Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover in the Catalogo del Museo Settala, mid-seventeenth century. Watercolor. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena (vol. 1, ms. 17)

Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), physician and second president of the

Royal Society—whose collection was to become the foundation of the

British Museum in 1753—owned two pieces that are listed in his

manuscript inventory and which still survive in a battered state. An

oblong cushion in much better condition, also in the British Museum, was

only acquired much later and illustrates the rise of ethnography as a

discipline in the nineteenth century, which led to the fragmentation of Kunstkammern all over Europe. It was first inventoried in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer

in 1674 but was deaccessioned by the Nationalmuseet in Copenhagen and

acquired by the Quaker and abolitionist Henry Christy (1810–1865), who

gifted it to the British Museum.

Luxury Cloth: Cushion Cover,

16th–17th century, inventoried 1674. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom,

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola.

Raffia; 9 x 20 7/8 in. (23 x 53 cm). British Museum, London

But how were these cloths originally acquired? We are slowly finding

out more about the web of European dealers, the international trading

companies, and the merchants who supplied collectors, but the cultural,

political, and trading exchanges in which textiles first changed hands

in Kongo itself are still a mystery. Did European visitors bring

examples of their own cushions to Kongo and commission copies in local

materials and techniques? Or did Kongo leaders commission them as items

of commerce, exploiting new markets? Either way, their presence in

European collections from the sixteenth century attests to the

fascination they aroused as virtuoso textiles, which made distant worlds

tangible.Wednesday, August 15, 2018

Les differents textilles

Le cheik

Les pagnes bordes

Les pagnes non bordes

Les pagnes du dessus

ndèngui

limenea

mbongos

Guinées

Ntango

Okouwre

Gombe

Le pagne du chef

indiennes

raphia moelleux Apimdji

raphia a l ananas

raphia au crochet

raphia imprimé

Raphia en soie

Raphia en lin

Raphia metalique

soie

indigo

Peaux

fibres

synthetiques

Polyster

Cretones

Organza

Boston or massachussety

Bantsuali les tissus de traite nkami couvertures rouges nta grands pagnes de raphia “chez les Kukuya, on tisse l’étoffe indigène (de raphia) la plus fine; elle est très recherchée et vendue extrême- ment cher” (ibid. 1. Pecile nous en décrit la technique et signale que “les Kukuya sont des maîtres de cet art; les pagnes raffinés dont se servent le roi Makoko (Tiol et ses épouses proviennent de ce pays” (Pecile 1887:450 et suiv).

Les pagnes bordes

Les pagnes non bordes

Les pagnes du dessus

ndèngui

limenea

mbongos

Guinées

Ntango

Okouwre

Gombe

Le pagne du chef

indiennes

raphia moelleux Apimdji

raphia a l ananas

raphia au crochet

raphia imprimé

Raphia en soie

Raphia en lin

Raphia metalique

soie

indigo

Peaux

fibres

synthetiques

Polyster

Cretones

Organza

Boston or massachussety

Bantsuali les tissus de traite nkami couvertures rouges nta grands pagnes de raphia “chez les Kukuya, on tisse l’étoffe indigène (de raphia) la plus fine; elle est très recherchée et vendue extrême- ment cher” (ibid. 1. Pecile nous en décrit la technique et signale que “les Kukuya sont des maîtres de cet art; les pagnes raffinés dont se servent le roi Makoko (Tiol et ses épouses proviennent de ce pays” (Pecile 1887:450 et suiv).

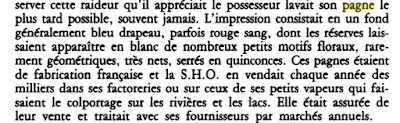

Coton Anglais

Ce tissu fut très apprécié par les gabonais au XIXe siècles.Une femme gabonaise qui se respecte dans

Ce tissu fut très apprécié par les gabonais au XIXe siècles.Une femme gabonaise qui se respecte dansLe Mpondé

Le tissu est fait a partir des écorces battues provenant d' un fiscus et

parfois mélangés avec le coton ou la laine pour le rendre souple.Les

premiers Habitants du Gabons s'habillaient en tissus d’écorces battues.

Le tissu est fait a partir des écorces battues provenant d' un fiscus et

parfois mélangés avec le coton ou la laine pour le rendre souple.Les

premiers Habitants du Gabons s'habillaient en tissus d’écorces battues.

Le tapa gabonias lourd est bien pour les ameublements et décorations.

Le dikonzi

Le Ngombu, masieli,ndengi,

Étoffes punu en raphia sous forme de patchwork en composé de plusieurs étoffes de raphia.Onamba

Tissus riche M'pongoue qu'on utilisait comme dessus.Le Madras Gabonais

Le Boston

Le Manchester

L'original et les africains.

Dutch Wax

Le coton brodé

Pagne rénovation

Je suis à la recherche des tissus traditionnels Gabonais , s'il vous plait si vous en connaissez le nom et les fibres qui les constituent faites-le moi savoir.

C'est une longue bataille mais on arrivera.

Contact-moi:

mujabitsi@hotmail.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)