Sunday, September 9, 2018

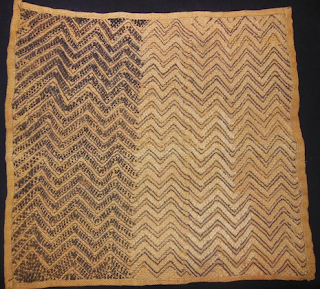

Pagne Kuba

In sub-Saharan Africa, where representative art has flourished for centuries, carvers and crafts people have typically taken for their subjects human figures, animals, plants, and elements of the natural world. Abstract art, meanwhile, has remained marginal. The textiles of the BaKuba (Kuba) people of the Democratic Republic of Congo are an exception. Although part of a tradition that stretches back 400 years, Kuba textiles have a strikingly modern look. They use improvised systems of signs, lines, colors, and textures, often in the form of complex geometric rectilinear patterns. Their appliqués are reminiscent of works by 19th- and 20th-century masters like Matisse, Picasso, Klee, Penck, and Chellida. This is no coincidence: all of those artists were inspired by Kuba design!"

"The most commonly known of the Kuba textiles are the cut-pile Shoowa or Kasai Velvets, named after the river along which the BaKuba live. Improvisation and irregularity characterize the Kasai Velvets. This is because the weaver works without a plan or preliminary sketching, though the model can occasionally be displayed on the cloth in advance using black thread. Often the design is built up from memory, repeating the most common designs and color combinations found in the region. The message conveyed is up to the artist, who is the only one who can explain what he or she intended to represent."

"Originally Kasai Velvets were used as currency, and were valuable products for trade and exchange. They could be included in the tribute villagers paid annually to the King, in the dowries of matrimonial exchanges, and in funeral gifts and offerings to the dead. They also served to embellish the royal court, cover the royal thrones, and decorate the King’s palace wall. Colonial agents and missionaries arriving in the Kuba Kingdom in the nineteenth century were fascinated by the Kasai Velvets, and encouraged women to produce more of them to adorn religious vestments for Catholic missionaries and decorate the interiors of European houses." This piece measures 18" x 20"

Friday, September 7, 2018

The Dress of Makoti

This is an example of the dress of makoti. To show respect and submission to the authority of her husband and parents-in-law, traditional practice dictated that a newly-married Xhosa woman would wear her ikhetshemiya (headcloth) low over her forehead, keep her shoulders covered, cover her hips with a blanket and wear a isishweshwe skirt and apron. She should stay with her parents-in-law for up to a year, a period during which her behaviour conveyed that she adhered to ukuhlonipha traditions of respect. Aspects of this practice are still present but are being eroded with urbanization. Head cloth, blanket and towel on loan from Siphokazi Mesele, nee Lindelwa Pamela Mbola, who wore them when she was makoti.

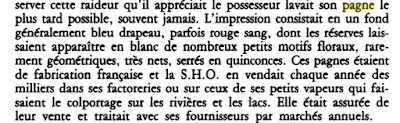

Blaudruck

Simplified resist-dyeing techniques were used to create a fabric of

small, white, regularly spaced patterns on a deep blue background. This

was known in Germany as 'blaudruck' (blue print). This fabric was

transformed into garments for work-wear and peasant-wear, and became

associated with European regional and Protestant dress, as well as

expressing nationalist sentiments. When German missionaries and traders

immigrated to the Eastern Cape and other parts of southern Africa during

the mid-1800s, they brought their 'blaudruck' with them and traded with

those they came in contact with. It became popular amongst women on

mission stations. This fabric was later adopted by IsiXhosa women in the

Eastern Cape to produce garments.

Indienne

One of the oldest artefacts in the isishweshwe collection, this dress is

an example of 'Indienne'. It is made of Indian cotton (chintz or

calico) and has a continuous pattern of delicate intertwined stems

bearing leaves and flowers. The dress originated on the Coromandel coast

of India in the third quarter of the 18th century. Indian chintz was

extremely popular throughout the eighteenth century, and was imported

into the Netherlands by the Dutch East India Company, thus making it

available at the Company's halfway station at the Cape.

IsiShweshwe and Colonialism

The

cloth known as amajamane, amajerimane or isishweshwe has its origins in

the East, and was originally made from cotton and blue dye from the

indigo plant. Through trade, it spread to different parts of the world

including the Cape, where it was initially worn by slaves, Khoisan and

colonialists. The earliest origins of isishweshwe can be traced back to

the craze for colourful indiennes (Indian cottons) which spread like

wildfire across Europe from the mid-1600s. The complicated techniques

for making multi-coloured indiennes in Central Europe were eventually

adapted to the use of one colour only: indigo.

Thursday, September 6, 2018

Wednesday, September 5, 2018

Raffia

Possibly Teke artist

Raffia cloth

(nkuta)

Date: Early 20th century

Medium: Raffia

Dimensions: H x W: 33.2 x 28.3 cm (13 1/16 x 11 1/8 in.)

Credit Line: Gift of S. M. Harris

Geography: Lower Congo-Kasai River region, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Object Number: 99-13-47

Search Terms:

Funerary

Trade

Object is not currently on exhibit

Woven

goods, such as cloth strips and fiber mats, were used in parts of

Africa as currency. Parties of the transaction used variations in width

and the quality of the weave as a means to negotiate value. Cloth was

also frequently used in connection with other currencies, such as brass

rods, thus lending additional leverage to the negotiation. Cloth or mats

of more or less uniform size were used for gifts, peace offerings,

payment from a son to his father upon attaining adulthood and payment

upon the birth of a child or the burial of a parent. Cloth currency was

also used as a tribute for a spouse who remained faithful or, by

contrast, as a penalty for adultery. In central Africa raffia woven

mats, stored flat or rolled into bundles, were a popular form of cloth

currency in the late 19th and early 20th century. Among the Teke

peoples, funerals of the wealthy and nobility required raffia cloths not

merely to cover the body but in abundance to ensure a proper status in

the "village of the dead."

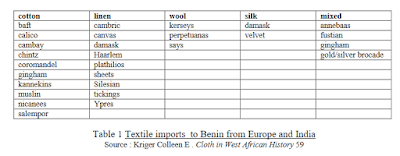

Cloths with Names’: Luxury Textile Imports in Eastern Africa, c. 1800–1885

In the nineteenth century, a vast area of eastern Africa stretching the

length of the coast and into the reaches of the Congo River was

connected by long-distance trade mostly channelled through the Omani

commercial empire based in Zanzibar. As studies have recently shown, a

critical factor driving trade in this zone was local demand for foreign

cloth; from the 1830s the majority of it was industrially made coarse

cotton sheeting from Europe and America, which largely displaced the

handwoven Indian originals. Employing archival, object, image and field

research, this article demonstrates that until 1885 luxury textiles were

as important to economic and social life in central eastern Africa,

textiles known to the Swahili as ‘cloths with names’. It identifies the

thirty or so varieties which élites — and, increasingly, the general

population — selected for status dress and gifts, instrumental in

building the commercial and socio-political networks that linked the

great region. Finally, it shows that the production and procurement of

most varieties remained in the hands of Asian textile artisans and

merchants; most prestigious and costly were striped cotton and silk

textiles handcrafted in western India, and in the southern Arabian

nation of Oman. European industrial attempts to imitate them were

hampered by several factors, including their inability to recreate the

physical features that defined luxury fabrics in this region — costly

materials, rich colours, complex designs and handwoven structures.

"Gabon" Textile

"Gabon" Textile

- Designer:

- Nathalie du Pasquier (French, born Bordeaux, 1957)

- Manufacturer:

- Rainbow, Milan

- Date:

- 1982

- Medium:

- Cotton

- Dimensions:

- 55 in. × 13 ft. 3 in. (139.7 × 403.9 cm)

- Classification:

- Textiles-Painted and Printed

- Credit Line:

- Gift of Geoffrey N. Bradfield, 1986

- Accession Number:

- 1986.398.3

- Nathalie du Pasquier was a founding member of Memphis. Barbara Radice, Sottsass’s partner, describes her as "a kind of natural decorative genius—anarchic, highly sensitive, wild, abstruse, capable of turning out extraordinary drawings at the frantic pace of a computer. . . . [Her works] are enthusiastic, explosive, exalted, elated, as striking as neon in a tropical night." Du Pasquier’s complex repeating patterns embrace all manner of influences, including African textiles, Cubism, Futurism, Art Deco, and graffiti. This work belongs to a series based on African patterns. Other designs are titled Kenya, Zaire, and Zambia.

Tuesday, September 4, 2018

Jadis

chaque

tribu

était

plus

ou

moins

spécialisée

dans

tel

ou

tel

artisanat;

les

Baduma

et

les

Mitsogo

excellaient

dans

la

confection

de

tissus

de

raphia

(ibongo),

les

Ngowè

dans

le

tissage

des

nattes

fines

à franges

(tava

yi

N gowe)

,

les

Batsangui

dans

le

travail

du

fer

(imyanga).

Ainsi,

jusqu'à

ces

derniers

temps,

les

Adyumba

étaient

renommés

comme

fabriquants

de

poterie

(ambono).

Sunday, September 2, 2018

Saturday, September 1, 2018

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)